Absolutely fascinating documentary. Saying it now, this is gonna be a long review, because this film is packed and to even give an outline of the setup is to dive into a thoroughly messy time in history.

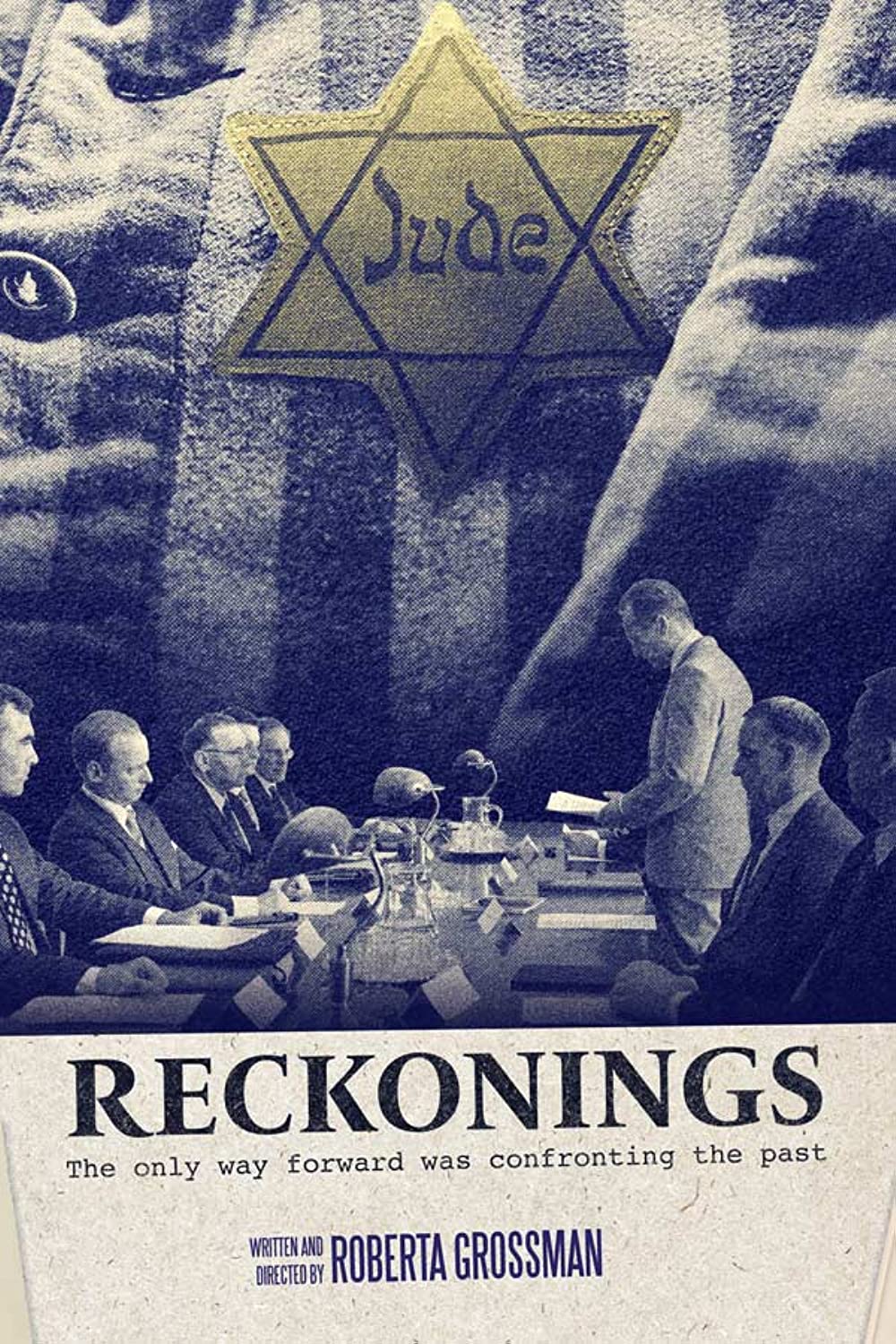

Reckonings outlines the story of how Germany came to agree to pay reparations for the Jews killed in the Holocaust. If you are thinking, “Aye, well obviously you would”, you don’t know how complicated this story is. If anything I wish this film had been longer, more detailed. I wanna go away and read more about the subject.

I knew absolutely nothing about the Luxembourg Agreement coming into this. I had never given much thought for how compensation came to be, as it seemed the most normal, natural, and only moral response. But it was a very different world in 1952. The Nazis didn’t evaporate at the end of the war, and they were still part of the social fabric of Germany. Even if someone wasn’t a card-carrying member, the entire population had been subject to years of indoctrination that they, their loved ones and their way of life were under attack from Jews, that Jews had been a legitimate and real threat, whose defeat was simple self-defence. To put it in disgustingly reductive terms, Germany had been defeated by the Allies, the Jews had been defeated by Germany, and that was just the way things were, like it or not; the idea that Germany would pay not only those who had triumphed over them, but also those who they had subdued seemed to fly in the face of logic. It was unprecedented.

And not popular. The German Chancellor Adenauer spearheaded the push for compensation to be given, and received a bomb in the post for his views. Even those who didn’t object on the basis of antisemitism, objected on the basis of self-interest. Germany had been bombed flat by the Allied forces. It had been economically destroyed by the cost the war. It had been split into two, and East Germany under the Soviets took absolutely no responsibility for actions of the Nazis. So West Germany, who I’m just gonna be referring to as Germany here, felt they had enough on their plate, and enough understandable excuses to get out of paying.

Luckily Adenauer wasn’t swayed. A devout Catholic, he was convinced something must be done for the victims of the Holocaust, and that Germany must show its rejection of the their legacy. When Jewish representatives came to the negotiating table, they expected to see the same old faces, the people who had thrived under Nazi rule and continued to enjoy power and status in the new Germany. What they got was Adenauer, a man who so vehemently spoke out against the Nazis that he was suspected, although incorrectly, of being behind the assassination plot that almost killed Hitler. He was lifted by the Gestapo for questioning, but managed to escape the interrogation centre. However they then lifted his wife and did god knows what to her to get her to tell them where he was hiding. She withstood everything until they threatened to bring in her children, at which point she caved and told them what they wanted to hear. Adenauer understood her decision completely and forgave it utterly, but she could not live with it and took her own life. He was a man well acquainted with the Nazi capacity for barbarity.

However, not everyone shared his commitment to ensuring the horrors of the Nazi regime were acknowledged and its victims made amends. His Finance Secretary Fritz Schaffer felt like the one billion dollars promised was just an utterly unworkable sum of money, and undermined the entire negotiation process by trying to barter down the price. He was trying to balance Adenauer’s push for compensation with the influence of Hermann Josef Abs, a banker who had been a Nazi collaborator and was now in charge of trying to argue down the Allied powers on terms of war reparations. Pincered between the two, and responsible for keeping Germany solvent in these tentative years after the war, he looked for any way to get that number down.

You can imagine how the Jews felt about that. It cannot be emphasised how deep the feelings were about these negotiations on the part of Jewish people. Every negotiator was there representing millions dead and hundreds of thousands still living and suffering from what was done. To look Germans in the eye and hear them quibble over pennies in the face of their loss was something the word ‘insult’ does not begin to cover.

From the get-go the idea of sitting down the Germans was utterly repugnant to many Jews. In Israel, when Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion suggested they hear the Germans out, Menachem Begin held a rally outside denouncing him as a traitor, and the crowd was so enflamed they attempted to storm the Knesset. Ben-Gurion argued, quite rightly, that the Nazis had stripped their victims of every financial asset they had, and to allow the Germans to continue to enjoy possession of it was a terrible injustice. He argued that it was Israel’s place to fight for the rights of the 700,000 Holocaust survivors within its borders. Even still, the motion passed by only one vote.

And while I have so far presented this process as a Germany vs the Jewish community negotiation, it was actually more complicated than that. Germany was jointly negotiating with the state of Israel and an international organisation set up to represent Holocaust survivors elsewhere globally. And all of Israeli politics also comes into play.

They were bankrupt after the Arab-Israeli War that led to the establishment of Israel and the Palestinian Catastrophe. After an all-consuming war on all sides against every neighbouring country, the survival and protection Holocaust victims was conflated with the survival and protection of the Israeli state, an attitude that went unchallenged at the negotiations and within this documentary. The means for the Israeli government to buy arms is put forward in the same breath as the means to feed and clothe refugees. And while this is a film that is packed with plenty already, and it is understandable that it wants to keep focus solely on the victims of the Holocaust, there is a big yikes! in the lacuna in this part of the story.

My favourite part of this film was Ben Ferencz, a wonderful man, who I was delighted to see again after his appearance in Getting Away With Murder(s). A life replete with good work, he pops up here as a negotiator on behalf of the international Jewish community, outlining the legal argument on which the basis of reparations should be made. A small man, with sharp, clever eyes, he is frank and fair in his assessment of the situation, direct and open in his interview. He has a calm and a kindness to the way he speaks that I find admirable. At 102 at the time of this interview, he is still incisive as ever. So glad he is still with us, the man’s a treasure.

As I said at the beginning, this is a long review, but even outlining the moving parts gives you some idea of just how packed this 75-minute documentary is. Deeply intriguing, great film.