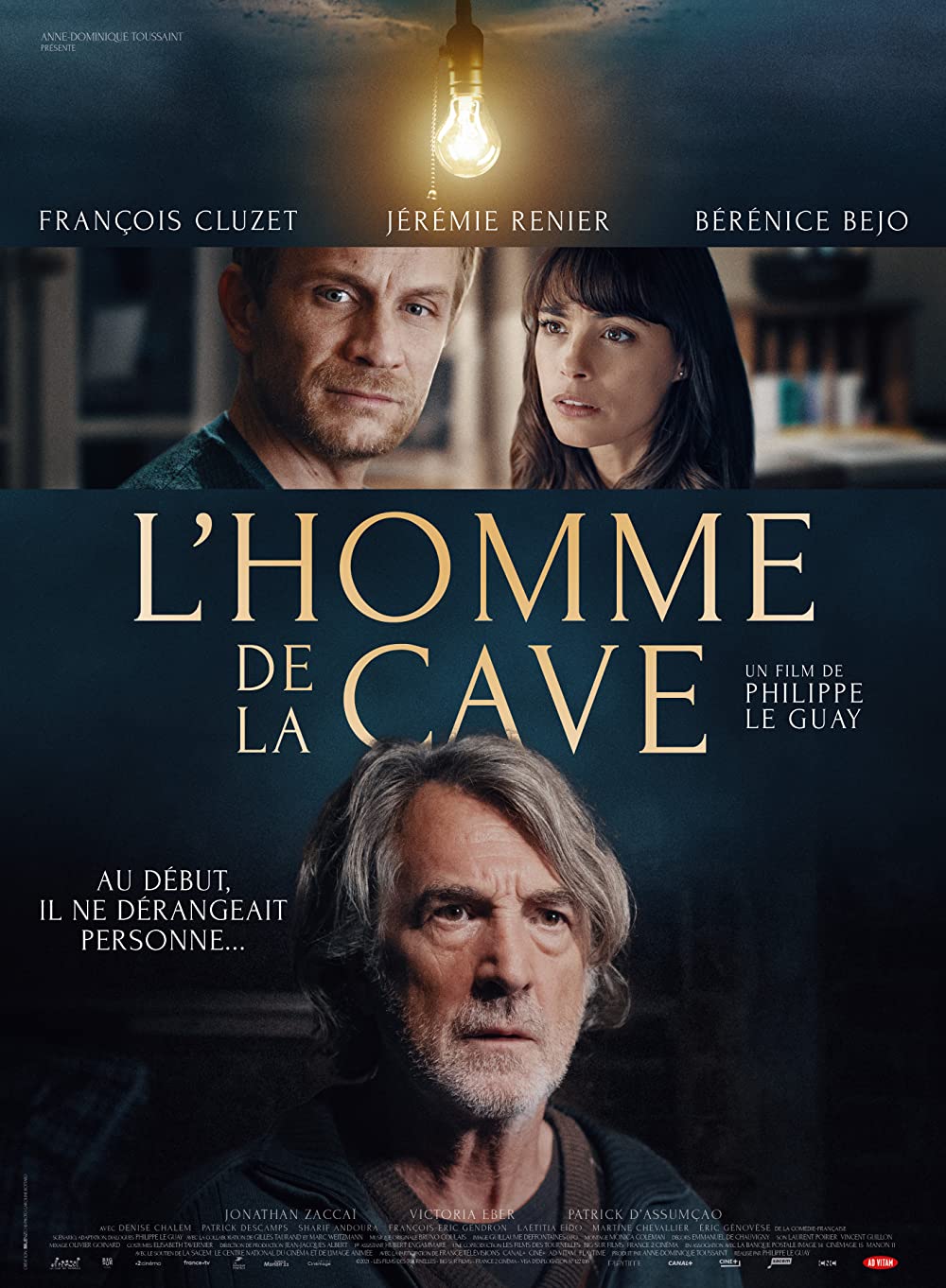

Really well put-together drama.

Simon lives in a nice middle-class block of flats, and to get some money to do up the kitchen, he sells the storage space he has in the building’s basement. It’s basically a swanky tenement with a sub-floor, that is divided into individual rooms for the tenants, each looking a lot like a coal hut. Simon finds a nice buyer, Mr Fonzic, who gives him a lovely sob story about his mother’s tragic passing and how he needs to clear out her place tout suite because he’s being victimised by her old landlord. Being a soft touch, Simon knocks a grand off the asking price and gives him his key early.

Until . . . he finds out who Fonzic really is. This bumbling, soft-spoken, sloped-shouldered, elderly History teacher is in fact a Holocaust denier who spreads his godawful hateful messages online. Fuck.

And here his problem begins. Because Fonzic moves into the basement room, using it as a base to tap out his cries of global conspiracy and fake news. The neighbours are disgusted and want to know what Simon plans to do about it. He starts down a litany of legal remedies but is stymied at every turn.

Meanwhile Fonzic is on his charm offensive, his “what, little old me?” bit. He sighs at how he has become a persona non grata simply for asking questions. How he is living in a poor bare basement, getting his drinking water from the courtyard hose tap, washing at the local swimming baths, is alone, is friendless, all for the harmless crime of being a free-thinker. Aw diddums.

The awful thing is this shit works. His assumption of victimhood is symbolically represented by the basement room itself. Simon’s great-uncle was killed in Auschwitz, and the last year he lived in the building was in hiding in that basement room. Fonzic’s physical occupation of it represents his appropriation of the story of Jewish persecution to manufacture a narrative of his own oppression. The room itself is at the very end of the lightless, windowless corridor beneath ground, its bare brick and wooden doors reminiscent of the entrance to the gas chamber.

And it also represents the underbelly of society, the things we want to forget about and be gone. The other neighbours in the building, they are initially appalled and find Fonzic’s presence distasteful, but they very much see him as Simon’s responsibility to deal with. They ask him over and over what Simon is doing about him, but never suggest ways to deal with Fonzic nor take him on as a problem themselves.

Indeed, as the film goes on, they grow warmer to him. Fonzic is, after all, just a bumbling, unshaven History teacher in an old coat. He’s so nice and polite. He waters the flowers. He’s already been through enough, living in the cold and dark down there, all alone, poor soul. All for holding an opinion! He’s not a monster, he’s not violent, he hasn’t done anything to Simon personally.

It’s Simon who looks like the crazy one, coming undone over the course of the film, as he goes from being so sure his reasonable objections to Fonzic’s occupation will be taken seriously, to finding himself running out of options, humiliated, isolated and having to stand by and watch the impact on his loved ones. His wife, who until that point, has always been ‘the Catholic in the family’ begins researching the family history and grows intensely frightened for the safety of her Jewish husband and half-Jewish daughter. She sees the clear threat Fonzic represents and is frustrated by Simon’s attempts to downplay it to keep her calm and docile. His daughter slowly falls under Fonzic’s sway, not understanding how everyone around her is losing their mind about this little old man, who is so kind and polite.

The film shows how tolerance for these thin-end-of-the-wedge types very quickly normalise a climate of fear and hatred, and have a devastating impact upon the people at whose expense they are tolerated. They don’t need to swing a punch or carry a gun to create a campaign of terror, and to swiftly change the perception of who belongs and who doesn’t belong.

Fuck Nazis.